Click on one of the following LINKS to view the main sections of the Site :-

Liverpool Collegiate History

Genesis

In the early part of the 19th Century there existed very limited facilities for the teaching of children, especially those from poor families. The sons of merchants would be sent to Dame Schools; there being over a hundred of such Schools in the Liverpool area. At the age of eleven they would transfer to private schools for three to four years, which for the most part would be run by local churches. It is estimated that about half of the 50,000 children between the ages of 5 and 15 did not attend school at all and most of them no doubt would be illiterate. The facilities and education in the Dame Schools were very poor. Children in Charity Schools (such as the Bluecoat School) had better education, albeit their treatment was often harsh.

Religion was considered to be central to good education, and in Liverpool both clergy and leading laymen decided to establish a day school of high quality with the Christian faith as its cornerstone. A meeting was held on the 12th July, 1839, 'to consider the best way to set up a new Protestant Institute in the Town for the education of all classes upon sound religious principles'. The first resolution made at this meeting was 'that it is expedient to establish an Institution in Liverpool for the general instruction of all classes combining scientific and commercial with sound religious knowledge'. Subsequently a Committee of Management was formed, comprising thirty-six members, representing in six equal parts the clergy, merchants, professional men and gentlemen, manufacturers, tradesmen and mechanics.

A target of £20,000 was set and fund-raising proved to be difficult. After six months only £10,000 had been donated. In addition to financial support, the patronage of a national figure was sought by the Committee and a number of persons were approached - unsuccessfully. Lord Stanley, later the 14th Earl of Derby and Prime Minister, accepted the patronage, whilst Lord Francis Egerton of the famous Bridgewater family became the first President of the Liverpool Collegiate Institution.

A number of sites were considered for the new

Institution and eventually it was

agreed to use a large site offered by Thomas Shaw in

Shaw Street on a substantial

mortgage.

The next task of the Committee was to appoint an

architect to design a building

for the Institution. Design was restricted to the

Tudor style and 29 competitors

responded to the Committee's invitation. Harvey

Lonsdale Elmes, then in his early

twenties, was successful. Earlier he had been

successful in being appointed the

Architect for St. George's Hall in Liverpool, which

is rated as one of the finest

classical buildings in the United Kingdom. Whilst he

saw the front of the Liverpool

Collegiate Institution completed, unhappily he died

before St. George's Hall was

built.

The following extract is given from the publication “The Picturesque

Handbook of Liverpool”, by H.M. Addey, which was published in 1849,

outlining the structural features of the Shaw Street Building -

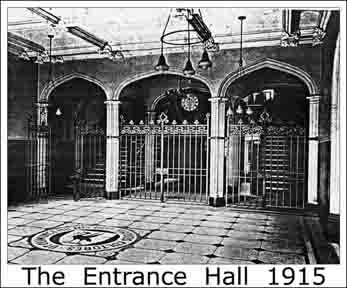

“The principal front, towards Shaw Street, is 280 feet in length, and comprises a centre and two slightly projecting wings. The magnificent arch, which rises above the central porch and the lofty Oriel windows, carried up through two stories, with the richly carved canopied niches, and statues of Lord Stanley and Lord Francis Egerton, surmounting them, convey an idea of grandeur which is rarely to be met with. The main building contains four stories, varying from 14 to 17 feet in height; but as the highest is lighted from the roof, only three tiers of windows are shown to the street, and the upper ones being combined together in a general composition, produce the grand effect of a single range of lofty windows. These four stories comprise 48 apartments, all 25 feet in width, and varying in length from 20 to 50 feet, and are appropriated as schoolrooms, a board room, secretary's room, a library, lecture rooms, museum and painting and sculpture gallery, the latter of which is 218 feet in length, and well lighted from the roof. There are likewise retiring rooms, wash rooms, etc. in each story, and three separate staircases. An octagonal building behind, contains, upon the ground floor, a series of dining rooms, kitchen, etc., and above a handsome, well ventilated lecture hall, 50 feet high from the floor to the ceiling, with two galleries, containing accommodation for 2,300 persons. A spacious music-room with rising seats for nearly 300 performers, opens from the lecturer's platform, through a lofty arch the whole width of the lecture hall, in which an organ is erected upon a grand scale”. “The lecture hall is approached from the grand staircase by fine wide passages, leading to the body and the galleries through numerous commodious doors. It is a fine structure, comprising five sides of an octagon, with two galleries above the body. The organ is situated at the back of the music room, and in the front and at the sides there are a series of seats declining by steps to the platform, which extends into the body of the hall, and is surrounded by a handsome railing. The hall is lighted from the roof by a large octagonal window, richly groined, gracefully dropping from the centre, and by five lozenge-shaped flat lights placed around it. The body and galleries are so constructed that all can distinctly see and hear the speakers. Indeed the hall has been pronounced by competent judges to be the best adapted for the purposes of sound, of all our large public buildings. The seats, which have backs to them, are exceedingly commodious in every respect, especially in affording space for the knees. On the evenings of Tuesday and Friday, lectures are delivered in this hall, to which non-subscribers are admitted on payment of an admission fee”.

“The foundation stone was laid by Lord Stanley, the patron of the Institution, on 22nd October, 1840. The Institution comprises three distinct day schools, at different rates of charge, with separate apartments, playgrounds, divisions of the lecture hall, etc., to each, so as to accommodate the three classes of society. The Bishop of Chester is the visitor, Lord Francis Egerton, the president; the Reverend Rectors of Liverpool, the chairmen; and the list of Governors, and the Board of Management, contain the names of the most eminent and influential of the clergy, merchants, bankers and tradesmen of the town. The course of instruction comprehends every useful and ornamental branch of education; and the religious tuition is in conformity with the doctrines of the Church of England. There are likewise evening schools, for the instruction of adults, in literature, art, and science; and from the amount of talent which the three day schools place at the command of the directors, these schools afford advantages of an extraordinary description to the inhabitants, upon the most moderate terms.”

It has now become custom and practice for the Collegiate Old Boys' Association to celebrate Founders' Day by having an Annual Dinner on a Friday in October, which is the closest to the 22nd. The venue for this event in recent times has been the Athenaeum in Liverpool, which is a splendid Institution and has an ambience which is very befitting for this occasion. In addition, the Governors of the Liverpool College kindly invite members of the Council of the Association to attend the Annual Founders' Day service, which is held in the Liverpool Cathedral.

Founders' Day - 22nd October, 1840

There were great celebrations in Liverpool on the day the foundation stone was laid. Following a two hour service in the Parish Church of St. Peter in Church Street (on the site of Woolworths' Shop in days gone by), a procession formed in the quadrangle of the Bluecoat School. (At our Annual Dinner at the Athenaeum we can look down on this quadrangle of the Bluecoat). Thousands lined the route from School Lane, Ranelagh Street, Lime Street, Islington to Shaw Street. The foundation stone was drawn by five horses and pushed by four more. On the stone sat six apprentice masons wearing white leather aprons bound in blue. In the procession came boys of the Blue Coat School in 'well kept ranks' followed by sixty clergy, four hundred gentlemen marching four abreast followed by their ladies in carriages. When the procession arrived in Shaw Street, a brass cannon fired a 'feu de joi' that shook the nerves of the ruder as well as the feebler sex. Before the stone was laid, a bottle of coins and papers was deposited in the foundations. The Blue Coat band played 'God Save the Queen' before leading the procession back to town for a public dinner, which cost one guinea for men and half-a-crown for their ladies (who were allowed to listen and watch from boxes and galleries). It is said that the ladies were provided with light refreshments. The assembled company drank some dozen toasts to each member of the Royal Family and other personages. Several members tried to speak at once and finally the Reverend Hugh McNeile, who came from County Antrim and was Minister of St. Jude's Church “roused the company to echo his cry 'Charge Chester, Charge! On Stanley On!” With a thousand voices shouting the call, the dinner ended and the Liverpool Collegiate Institution was well and truly launched.

The Building of the School

The contract for the building was given to John Tomkinson, who tendered to put up the whole school for £21,379. The School was opened officially on a wet Friday morning, 6th January, 1843.

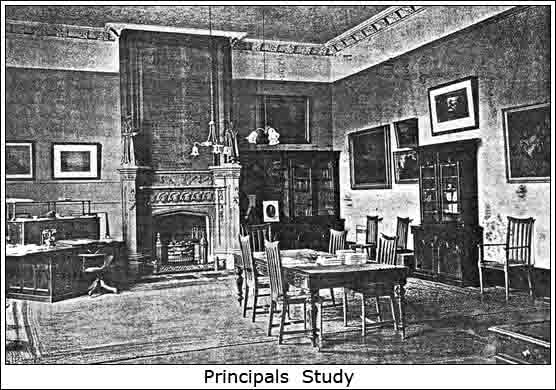

The façade was of pink Woolton sandstone with ten Gothic windows, a central porch arch which extended to the full height of the building, and at either end a niche bearing the statues of the patron and president. Other features included the Board Room with a tall chimney piece of Talacre Stone, bearing the names of the president, directors and other officers of the Institution and carved with the coat of arms of the rectors of Liverpool and donors of £1,000. (This room became the study of the of Headmaster of the Liverpool Collegiate School and now the chimney piece has a splendid position on the first floor of the building at the top of the central staircase).

The opening ceremony itself was attended by the usual gallery of important personages of the day, and was marked by an impressive speech from W.E. Gladstone, who presided.

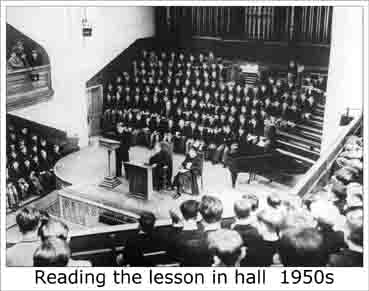

The School Hall

The school hall was the only large public meeting hall in Liverpool in the early 1840's, and was used for concerts, lectures and meetings. The Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra used it before the original Philharmonic Hall was opened.

Academic achievement and Financial problems

Academically the Institution went from strength both

in University entrance and

in the new Oxford and Cambridge public examination

to be taken by boys of 18 and

16 years. In 1864 the cumbersome title of the

Collegiate Institution was changed

to the Liverpool College, since at that time it was

commonly known as 'the College'.

It was significant that boys could transfer from the

Lower School to the Middle

School and from the latter to the Upper School. In

1865 there were 879 boys in the

College, with 185 in the Upper School. In 1869 six

boys gained open scholarships

and a tradesman's son became Senior Wrangler at

Cambridge University. However, whilst

the Upper School was thriving, the Middle and Lower

Schools were losing money. By

1878 the position of the College was becoming

perilous, but the link that had been

forged with the Liverpool Council of Education

(since its foundation in 1874) saved

the day. This body was established to promote and

encourage elementary education

by every means. The Council set up scholarships to

allow Liverpool Board School

boys to attend the College - it was possible for

them to work their way to the highest

academic honours at Oxford and Cambridge.

The Committee of the College agreed, after much

persuasion, to purchase a house

in Lodge Lane, to which some of the boys in the

Upper School moved in 1884. The

Lodge Lane premises became an exciting place

compared with the Shaw Street premises

and attracted many more pupils. All of the Upper

School boys were transferred in

1890 to Lodge Lane - the Headmaster spending most of

his time there (and only two

afternoons a week at Shaw Street)

In 1891 the City Council voted £400 per annum for technical instruction at Shaw Street. Through the 1890's the Middle and Lower Schools lost £150 per year. The boys were the sons of clerks, working men and small tradesmen and had come from public elementary schools. The fees, £4 and £5 per year, were already a strain on the pockets of parents.

The Liverpool Collegiate School

On the passing of the Education Act, 1902, the City Council created an Education Sub-Committee with a responsibility for the introduction of a new scheme of secondary education. In 1904 the City Council commissioned a report on Secondary Education and soon after its publication, negotiations were started for the Council to take over the Shaw Street premises. The Old Boys of the 'College' embarked on a battle to save the Shaw Street Schools, because they felt that the three schools of the old Liverpool Collegiate Institution had a common tradition, which should continue. They endeavoured to raise funds, but unsuccessfully, and eventually the fight was lost. On Wednesday, the 3rd July, 1907, the Shaw Street Schools were sold to Liverpool Corporation for £12,000. The portraits of the founders were removed to the College in Lodge Lane and the Shaw Street Schools reverted to a form of their original title and became the Liverpool Collegiate School, which was to achieve a greatness of its own in the years that followed.

Despite efforts by the Governors of the School to retain it as a Grammar School, it was changed to a Comprehensive in 1973, and ceased to exist in 1985.

Acknowledgements

This brief history of the Liverpool Collegiate School has been compiled from data in the book written by H.S. Corran, B.A., Ph.D. on 'A short history of the School - 1908 to 1985'. He was a former pupil of the School and an Earl of Sefton Scholar 1926-33. Information has also been extracted from the Liverpool Education Department publication 'Yesterday's Schools 1880 - 1980'

© Liverpool Collegiate Old Boys' Association (2018)